IMD business school for management and leadership courses

Published on November 21st, 2025

How Xiaomi Broke Every Law of Corporate Death

Published on November 21st, 2025

On March 28, 2024, at 7:00 p.m. Beijing time, Lei Jun of Xiaomi (pronounced shyow‑MEE) stepped onto the stage. He appeared visibly thinner than usual. The 54-year-old CEO paused, surveying a crowd of engineers and journalists. He described the project, which involved building an electric car from scratch, as “the last major entrepreneurship project” of his life.

Then the car was revealed: the Xiaomi SU7. The crowd erupted as the specs flashed across a giant screen: faster than a Porsche Taycan, longer range than a Tesla Model S, and priced ¥30,000 cheaper than a Model 3.

Lei stood there and calmly told the crowd, “In the past three years, we’ve invested over ten billion yuan and dedicated 3,400 engineers to this project.”

At this point, the order counter went live.

Ten thousand orders arrived within the first four minutes. By the 27-minute mark, that number surged past 50,000. The entire 2024 production run was gone within a single day.

In the days that followed, reports surfaced of customers lining up until 3 a.m. just to secure a test drive. The “Apple of China” had just built a car, and the market was in collective disbelief.

How could it not be? Ralf Brandstätter, CEO of Volkswagen Group China, would tell a German newspaper that “China’s car market has lost all reason.” 130 brands were now fighting for survival in the electric vehicle space, according to Volkswagen.

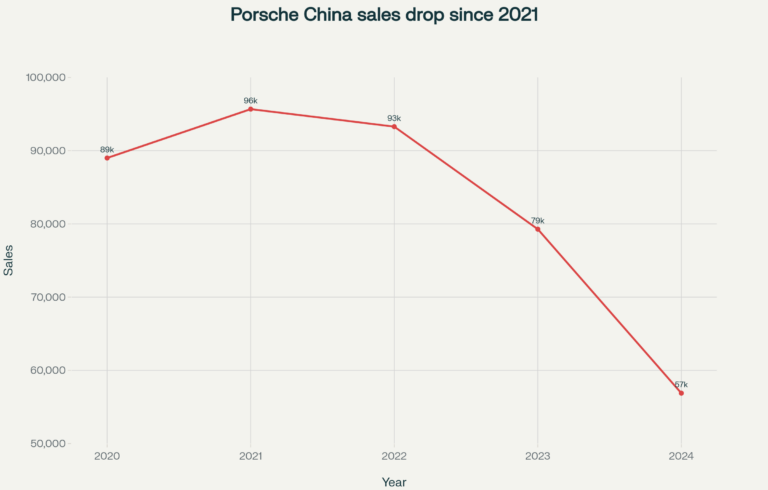

Meanwhile, Porsche, formerly untouchable, was slashing 30% of its China workforce as sales plunged from 95,671 vehicles in 2021 to barely 60,000 in 2024. In an email to 37,000 employees, CEO Oliver Blume admitted, “Our business model no longer works in its current form.”

China’s EV market wasn’t just competitive. It was a meat grinder.

But Lei Jun had seen a meat grinder before. He had stood at the edge, staring at oblivion, and somehow found a way back. And he lived to tell the tale.

The Making of a Unicorpse

Summer 2016. It was past midnight in Beijing, and Lei Jun was pacing a near-empty conference room. Only a few aides remained. Once hailed as the “Apple of China,” Xiaomi was now in freefall. Shipments had crashed from 70 million in 2015 to just 41 million in 2016.

Once the country’s top phone brand, Xiaomi had fallen to fifth place. The press had developed a new word for it: “unicorpse.” That is, the fallen unicorn.

No company had ever clawed its way back after losing that much ground. Not Sony Ericsson, not Motorola, and not HTC. Nobody ever had.

What happened? In 2014, Xiaomi was riding high. It had become China’s number one smartphone vendor, edging out Samsung with 12.5 percent market share. The startup was barely four years old. Yet it hadn’t even begun as a phone maker. It started as a hacker experiment called MIUI, a customized version of Android that Lei Jun released on online forums for “enthusiasts” to try.

That was the original magic: Xiaomi didn’t build a product and then look for customers. Instead, it built a community first and then asked what it wanted.

The MIUI forum became a living organism, a co-creation platform. It was essentially an Android skin where users could request features, test new builds, and watch their ideas come to life each week. More than 78 million users logged on to suggest improvements, test weekly versions, and help one another debug. One early fan wrote, “I log on in my spare time every day. It makes me very happy and relaxed.”

The users were fans who formed a movement. They felt ownership.

By 2011, the community had grown to 300,000 die-hard believers who wanted a phone to call their own, and Lei Jun decided to build it for them.

Preparation for the first launch became startup legend. The presentation team locked themselves in a meeting room for six weeks. On the door, a single A4 sheet carried one handwritten word: Madhouse. Lei Jun, a software veteran obsessed with detail, reviewed every slide of the 96-page PowerPoint. He insisted that the price reveal “fall onto the paper in larger font.”

On August 16, 2011, Lei Jun walked on stage in a black polo shirt, just like his idol Steve Jobs. The “Madhouse” work paid off. The crowd erupted, chanting a new nickname: “Leibos,” which was a fusion of Lei and Jobs.

The phone, the Mi 1, was a sensation. It packed a high-end dual-core Qualcomm processor, rivaled Samsung’s best, and cost less than half as much. The first 100,000 units sold out in under three hours.

The triumph cemented what Lei Jun called the “Triathlon” model:

- Sell hardware at near cost to build a massive user base. Margins were rumored to be less than seven dollars per device, compared with Apple’s seventy.

- Go online only to skip retailers, cut marketing costs, and create frenzy through flash sales.

- Monetize the base through high-margin MIUI services such as themes, games, and ads.

For a time, the Triathlon was unstoppable. Shipments increased by 226 percent in 2014 alone. Xiaomi had sold 61 million phones. By the third quarter, the phone was number one in China and number three in the world, trailing only Samsung and Apple.

Investors couldn’t resist. They poured in capital, valuing the four-year-old company at US$45 billion. It was the most valuable startup on Earth. Every data point, every flash sale, and every chant of “Leibos” seemed to confirm Xiaomi’s magic. Time named Lei Jun one of the world’s 100 most influential people. He started to think he’d discovered a universal law of business.

As it turned out, he had only found a brilliant strategy for a niche.

YOUR WINNING MOVE ISN’T A UNIVERSAL LAW

Ask yourself: What percentage of my total market am I actually playing in?

If you’re dominating 20% but ignoring 80%, you’re not winning. You’re just early to the decline.

The Darkest Hour (2015–2016)

The fall came faster than anyone expected. Just two years after its peak, Xiaomi was gasping for air.

The company had built its empire on online flash sales, with those lightning bursts that sold out in minutes. The model worked brilliantly when it was novel. However, online sales made up only about 20 percent of China’s smartphone market. Xiaomi had bet everything on the 20 percent and ignored the other 80.

Meanwhile, Oppo and Vivo flooded rural China with more than 200,000 retail stores. These rivals offered margins as high as 20 percent to retailers and plastered blue and green billboards across every tier-two and tier-three city. They paid Leonardo DiCaprio to front their ads and splashed cash on the IPL cricket league. The pair would hold nearly 30 percent of the market by 2016.

Cracks actually began to appear in 2015. That year, Xiaomi set a bold target of 80 to 100 million handset sales. But it fell short, shipping only around 70 million units. Annual growth, which was once explosive, had slowed to about 15 percent.

The very strategy that had made Xiaomi unstoppable before was no longer working. Lei Jun had to kill his own dogma. What emerged was nothing short of a radical pivot.

THE HARDEST PIVOT IS KILLING YOUR OWN MAGIC

Ask yourself: Am I humble enough to see change coming, and brave enough to act before I’m forced?

You will eventually have to dismantle the very thing that made you successful. Not because you failed, but because the world moved.

Xiaomi had always called itself an internet company that happened to sell hardware. Now it would also become a retailer, but in a distinctly Xiaomi way.

In September 2015, Xiaomi quietly opened the first Mi Home inside a Beijing mall. It felt like a technophile’s bazaar, where phones sat beside rice cookers, scooters, and air purifiers. When phone sales faltered the following year, Lei Jun doubled down and brought in Tim Kobe, the architect behind Apple’s Fifth Avenue flagship, to design a new wave of Mi Homes. These bright, minimalist stores sold everything from smartphones to copper feng shui gourds said to bring luck and balance.

It was more like Costco-meets-Ikea for geeks. But Xiaomi didn’t invent everything it sold.

Behind the scenes, co-founder Liu De, a designer trained at ArtCenter College of Design, had quietly assembled an ecosystem of more than 210 partner companies by 2018. Xiaomi typically held 20–25% stakes in ventures like Huami (fitness trackers), Ninebot (which later acquired Segway), Smartmi (air purifiers), and Roborock (robot vacuums).

Xiaomi provided the capital, brand, and supply chain muscle, while the startups brought the ideas. Together, they built the shelves of Mi Home. The collaboration became a pipeline: Xiaomi mentored, standardized, and showcased their best products across Mi Home locations nationwide.

Soon enough, dozens of Mi Homes appeared across China’s biggest cities. Then hundreds followed.

Wang Xiang, Xiaomi’s senior vice president and a former Qualcomm executive, called the strategy “planting a garden.”

“Buying a phone or TV is a low-frequency event. But what if you also need a Bluetooth speaker, or a rice cooker, or the first affordable air purifier in China?” he asked. “Each one of those products is best-in-class and costs less than existing ones…. So customers keep coming back to see what’s new.”

The strategy worked. Mi Home stores became money machines, generating roughly ¥240,000 per square meter each year. A typical 200-square-meter shop earned ¥48–52 million annually. Apple was the only company to beat that figure.

A Beijing family might stop by for a smartphone repair and leave with a smart kettle and a matching set of Mi suitcases. Each purchase drew them deeper into the Xiaomi orbit.

By May 2018, Xiaomi had more than 400 Mi Home stores in over 50 cities. Lei Jun announced plans to reach 1,000 the following year. Xiaomi was no longer “online only.” Now it was meeting customers face to face, from Beijing to Chengdu.

CREATE REASONS TO COME BACK

Ask yourself: If your customer needs you only once every two years, do you have a relationship or just a transaction?

Build a garden, not a single product. Create small, frequent touchpoints so people return not because they must, but because they want to see what’s new.

Then, in January 2019, another bold stroke happened. Xiaomi split its Redmi brand into a fully independent sub-brand: Redmi would focus on value and online sales, while Mi would chase the premium market and lead the new retail expansion. It was a direct challenge to Huawei’s Honor line.

At the launch, Lei flashed a slide that read, “Take life and death in stride; if you’re not convinced, let’s fight.” The audience roared, and the old swagger was back.

The comeback was undeniable. Xiaomi shipped 90 million smartphones in 2017, which was a 74 percent jump from the previous year. Then it topped 100 million in 2018 and 125 million in 2019, marking a full recovery and more. “Only by winning in China can we win in the rest of the world,” Lei said.

He wasn’t done yet. He wanted one additional big bet.

Why This Only Works in China

In my executive classes, people often ask me if the Xiaomi story could have happened anywhere else. Could a company reinvent itself that fast, not just in Beijing or Shenzhen but in New York or Amsterdam? Is it about culture, or something deeper?

The barrier in the West today, I explain, is not capital or talent. Rather, it is the absence of a hardware ecosystem.

Walk into a Mi Home store and look around. Every shelf is packed with gadgets, built by contract manufacturers like Foxconn, from young Chinese startups. The parts come from nearby industrial clusters where suppliers, mold makers, and assembly lines sit within a short drive of one another. If a mold is off by a fraction, an engineer can walk the prototype across the street and get it fixed before lunch.

Upstream, the supply chain is equally dense. China controls the raw materials, from rare earths to iron, copper, and the petrochemicals that make plastic casings. Reinvention at Xiaomi’s speed is possible only in a country where the entire value chain is within reach.

YOU CAN’T SUCCEED ALONE IN THE WRONG PLACE

Ask yourself: Am I in an environment that supports what I’m trying to build?

Speed doesn’t come from trying harder. It comes from operating where the levers are within reach. Or are you burning energy swimming upstream when you could move to where the current runs fast?

Lei Jun’s turnaround was not only about strategy. He happened to operate in a place where every lever of production was close enough to pull.

It’s no coincidence that Xiaomi’s rise occurred after Apple took root in China. Tim Cook’s mastery of supply chains did more than make iPhones cheaper; it built the industrial rhythm that companies like Xiaomi could later borrow. That’s why to understand how Lei Jun could move so fast, you have to go back a decade earlier.

Ever since the first iPhone was assembled in China, Apple engineers from Cupertino lived on Foxconn’s factory floors in Zhengzhou, fixing problems that no one else could. A misaligned screw meant stopping the entire line. “Close enough” got you removed from the program. Grace Wang, who would later found Luxshare, was there as a young manager watching this unfold. When Tim Cook visited her plant decades later in 2017, she told him, “Apple’s stringent requirements have profoundly impacted Luxshare. We have closely followed Apple, and this alignment has propelled us toward growth and prosperity.”

Here’s the translated version: You taught us impossible standards, and we made them our own. (For those curious, I wrote earlier about the rise of this “red supply chain.”)

The ecosystem never vanished. The tooling stayed. The supplier networks stayed. The engineers who could meet Apple’s standards kept getting better. In Changsha, a glass factory learned to survive 24-hour tool changes. In Ningbo, a camera shop kept a second line warm in case a defect upstream forced a swap at midnight. Lens and Sunny reached optical yields that were previously thought possible only in Japan.

Apple asked for the impossible. The Chinese were the only ones who said yes.

Over time, repetition became ritual. Week after week, ritual became muscle memory. Then luck found Lei Jun.

The Vacancy

In May 2019, Washington struck. Huawei was blacklisted overnight. Xiaomi’s fiercest Chinese rival suddenly lost access to Google’s Android ecosystem, the lifeline of its global phones. For Huawei, once the world’s number two smartphone maker, it was a death sentence. Within months, sales in Europe collapsed.

Xiaomi moved fast. Within weeks, its marketing teams flooded Europe, cutting deals with carriers and retailers that Huawei used to own. In Berlin’s MediaMarkt stores, sales staff began steering customers from the Huawei display to Xiaomi’s new line, claiming “same specs, lower price.” Shoppers loved it.

By mid-2021, Europe’s phone market had a new ruler. Xiaomi shipped 12.7 million smartphones that quarter, a 67 percent leap from the year before, according to Strategy Analytics. It was the first time the Chinese brand surpassed Samsung to claim the top spot. “Consumers have been impressed by Xiaomi’s cost-effective devices,” said Boris Metodiev of Strategy Analytics. A Chinese analyst put it more simply in the Global Times: “Xiaomi quickly filled the market gap left by Huawei.”

LUCK FAVORS THOSE WHO ARE PREPARED AND POSITIONED

Ask yourself: Are you building your capacity before the gap appears?

You can’t control when opportunity arrives. But you can control whether you’re ready when it does. That’s how luck finds you.

While the Redmi line flooded the mid-tier market with volume models, the Mi brand began to push upward. The Mi 10 series in 2020 carried a 108-megapixel camera and Qualcomm’s top-end Snapdragon chip. It was also Xiaomi’s first flagship priced above six hundred dollars. How did Xiaomi pull that off? Part of the success came through its own R&D, but even more of it was through the supply chain that Apple had trained.

Lei Jun placed his bet on overseas expansion just as Huawei fell. It looked like foresight. But it was also luck.

The Last Bet: Xiaomi’s Drive into Electric Cars

Fast forward to spring 2024. All the pieces of China’s industrial machine were in place: trained engineers, world-class suppliers, and hyper-efficient factories, ready for Xiaomi’s boldest gamble yet. On March 28, Lei Jun stepped onto a Beijing stage to unveil Xiaomi’s first car, the SU7.

But the SU7 wasn’t a standalone product: It’s the ultimate entry point into Xiaomi’s software system. Every SU7 runs on HyperOS, the unified operating system that powers phones, tablets, smart homes, and cars.

Slide into a Xiaomi car, and your phone’s apps, maps, and music instantly appear on the 16-inch dashboard. The SU7 mirrors your phone or tablet with a single tap, with no clunky Bluetooth handoffs. There’s no Apple CarPlay connect and disconnect.

You can pin WeChat, Spotify, or TikTok to the home screen and run them like apps on a tablet, in 3K and ultra-high definition. The car is a rolling Xiaomi device.

INTEGRATION BEATS INNOVATION

Ask yourself: How can I make what I have work together so well that leaving feels like loss?

Create a network of skills and projects that reinforce each other.

Stop asking “What’s the next big thing?” The SU7 isn’t revolutionary because it’s faster than a Porsche. But it works seamlessly with everything else you already use.

It also makes financial sense. By the second quarter of 2025, 60.8 percent of Xiaomi’s revenue came from non-smartphone businesses. This had never happened before in Xiaomi’s history. Finally, the “Triathlon” model of hardware, internet services, and new retail was making sense. For one thing, the internet segment earned 75 percent gross margins.

China’s industrial base, with training from Apple and Tesla, supplied the parts and the factories. Xiaomi supplied the fan base, distribution, and ecosystem. The SU7 now brought everything together.

More devices sold → More users in the ecosystem → More service revenue → More investment into new devices and stores

A car just happens to be the newest device. A dealership just happens to be another store.

Only by winning in China, the world’s ultimate hardware market, as Lei Jun insists, can Xiaomi win the rest of the world.

If you’re in your own valley right now, remember this: The phoenix isn’t born in a moment of inspiration. It’s built through a thousand small decisions to keep going when no one’s watching.

Your comeback isn’t ahead of you. You’re building it right now.