As recently as 2007, the list of the world’s most valuable companies was dominated by one industry – oil.

Fast forward to 2017, and this list had been completely transformed by technology companies. Tencent, Alibaba, Facebook, Amazon, Alphabet and Apple had all joined Microsoft on the list of the top 10 wealthiest companies on the planet.

These companies are all, of course, famously known as “disruptors”. But what else do their business models have in common, asked Goutam Challagalla, Professor of Strategy and Marketing at IMD, on day one of Orchestrating Winning Performance in Dubai.

They are also – crucially – all platform businesses, Professor Challagalla explained. They make money by connecting two parties together, with Apple’s business model of connecting us to app developers being perhaps the most famous, not to mention lucrative, example.

Uber, Airbnb and Booking.com are just some of the companies that have also used this model to dominate both the industries in which they operate and the everyday lives of people all over the world.

Ripe for disruption?

But change could be on the horizon, Professor Challagalla said. Could the likes of Uber and Airbnb, huge disruptors of traditional industries, themselves be ripe for disruption?

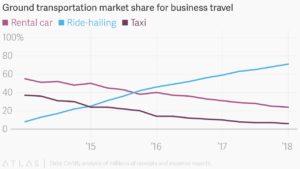

Take ride-hailing apps, for example. In 2012, their presence in the US was minimal; just 1% of rides taken was with ride-hailing companies. By 2018, that number had grown to 88% – a phenomenal level of growth.

Can this level of dominance possibly be challenged? Yes, said Challagalla, but only if those companies looking to “disrupt the disruptors” have the right strategies in place.

Traditional methods of differentiation do not work, Challagalla added. If you want to challenge Uber, for example, then you need to fight scale with scale.

This is exactly what Estonia-based Bolt (formerly Taxify), a company that is looking to challenge Uber’s dominance, tried to do when it launched in London in June 2019 with an impressive 20,000 registered drivers.

Nevertheless, Uber is still responsible for 5 billion trips a year, and disrupting something this powerful will take time.

While this happens, challengers must focus on the principles of how this disruption could take place. “Don’t focus on the disruptor,” Challagalla said, “focus on the type of disruption.”

Rules of engagement

Rule number one – change the rules. “If you want to disrupt a market leader, never play by their rules,” Challagalla said, “because they have mastered them. Doing the same thing will only work 5% of the time.”

Another key principle is to turn the strengths of these major players into weaknesses. Uber takes 28% commission from its drivers, while Booking.com requires 20-35% – numbers which represent unbelievable power, but one that isn’t immune to challenges from rivals that are willing to charge less (something that Bolt is doing by charging its drivers less to use its platform).

Some new companies even believe they can grow while charging zero commission, said Challagalla. So how will they make money? Some of them are using cryptocurrencies to make and receive payments, relying on the value of these going up to generate revenue. But this is, of course, speculative, and cryptos are treated with suspicion by governments around the world.

It is weaknesses like this that suggest this transition, this disruption of disruptors, won’t happen overnight. “We’re talking about the next seven, eight, nine years”, said Challagalla, “rather than the next three.”

Where will we see this change first? In Europe, said Challagalla, where regulators already have their eyes on how data is being used, then the United States. China, which is currently much more open to sharing of data, will take a bit more time, but there are signs everywhere that a new architecture is being created that could disrupt the technology industry yet again.