IMD business school for management and leadership courses

Sustainability

What social science teaches us about the energy transition – 5 questions for executives

by Amanda Williams, Knut Haanaes Published May 14, 2025 in Sustainability • 6 min read

Should you lead or follow, move fast or slow, go it alone or seek partners? Here’s how to get the key decisions right when aiming for a sustainable transformation.

Social scientists have been studying sustainable transitions for decades, and one thing is clear: transitions occur in complex and contested socio-political contexts. Although climate science demonstrates the urgent need for systems to decarbonize energy sources, these transitions are often chaotic, time-consuming, and prone to setbacks, even when the necessary technologies are available. One reason is that no transition occurs without the emergence of new societal actors and technologies that disrupt the status quo.

Social research seeks to understand how large-scale societal transitions occur by identifying key dynamics and changing mechanisms. The questions raised by the social sciences can teach business executives valuable lessons about the current energy transition.

Simply put, a transition is a change within a system from one state to another. In the context of sustainability, a system changes from an unsustainable state to a sustainable one. Transitions are characterized by nonlinear dynamics and disruptive shifts.

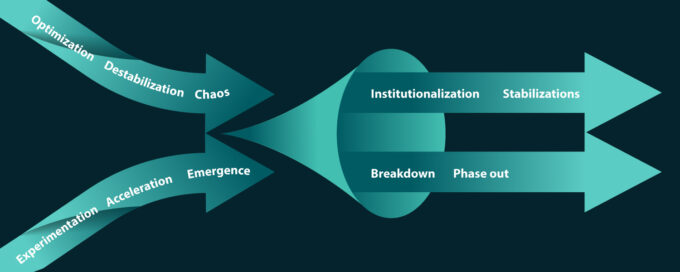

Central to transitions theory is the notion of a regime or the dominant unsustainable system that is locked in. For example, certain components of fossil fuel-based energy systems, such as drilling infrastructure, energy plants, and transmission lines, make up a system that, in its current state, is efficient and affordable. However, it is also “locked in” because changing it would be costly and time-consuming. Emerging niches, driven by networks of actors, intervene in the regime to disrupt the dominant system and promote the adoption of novel and more sustainable energy solutions such as solar, wind, or hydropower. The transition occurs when a regime is destabilized by a niche and phased out. A transition is complete when, often out of chaos, a new order is stabilized. The figure below illustrates this shift, which can be considered a paradigm change.

Question 1: Disrupt or be disrupted?

Any transition involves one system being disrupted by another. Key to those disruptions is innovation: an unsustainable system will be transformed if a new technology disrupts it. Companies decide which technologies to develop and invest in.

Those who hold on to the old regime benefit from efficiency and short-term profits from industry lock-ins, but will be phased out in the long term. Kodak is frequently cited for failing to adopt the digital photography transition early enough, which is considered a key reason for its decline. Those who decide to disrupt will face short-term uncertainty but will be among the first to benefit when the new system emerges.

The Danish energy company Ørsted is leading the clean energy transition and, despite recent setbacks and challenges, has found it to be the right approach financially, strategically, and environmentally.

Partnering enables companies to leverage the unique resources and skills of different sectors, thereby helping to develop innovations and create conditions for the emergence of new systems.

Question 2: Partner or go alone?

Companies deciding to be disruptors can choose between collaborating and independently developing new technologies. Societal challenges are so extensive that partnerships are often necessary to create meaningful change. Partnering enables companies to leverage the unique resources and skills of different sectors, thereby helping to develop innovations and create conditions for the emergence of new systems.

There are numerous partnerships to consider to accelerate the energy transition. The Future of Climate Cooperation project tracks the number of alliances, and by 2019, 250 climate partnerships had already been registered. Partnering is not easy and may slow progress; therefore, the conflicting goals, interests, and motivations should be carefully considered.

Acting early comes with a steeper learning curve.

Question 3: Accelerate or delay?

Timing is a key issue, especially in today’s political environment. The speed of the transitions will be determined mainly by when executives decide to act. One strategy might be to wait for others to make the first move, then learn from their mistakes and build on their progress. Another strategy is to act with urgency. The effects of climate change are already manifesting along supply chains and devastating societies around the globe.

Acting early comes with a steeper learning curve. Tesla was one of the first movers in producing electric vehicles, and its first-mover advantage in the US market can be attributed to competitors’ responses, product differentiation, and favorable public policies. Markets and policy situations are rapidly evolving as competitors have begun to erode Tesla’s profits. Still, the company remains one of the few that have generated profits on electric vehicles. Strategically, companies must ask themselves whether they should be first, early, or late movers.

One interesting example of the value of following an innovator is the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), established by WWF in 2004 to promote the growth and use of palm oil products.

Question 4: Visionary or follower?

At the forefront of any transition is a clear vision, well-defined expectations, and beliefs about an alternative future and how to achieve it. Different methods or tools, such as future-back approaches, back-casting scenario planning, strategic foresight, or disciplined imagination, can all be used to develop a vision.

The approach can be used to envision where you would like to be in the future and then define the steps needed to get there. Leading the development of the vision can have competitive advantages, such as actively influencing the agenda and being at the forefront of innovation and creativity. Following an already established vision constrains possible innovation pathways, but costs less. One interesting example of the value of following an innovator is the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), established by WWF in 2004 to promote the growth and use of palm oil products.

The RSPO has over 5,000 members from 94 countries, including many global food companies, and was established following non-governmental organizations’ concerns about the environmental impacts of palm oil production. No individual company could have had the same impact alone.

Question 5: Shape policy or adhere to it?

Governmental policy can support or hinder sustainability transitions because policies determine the rules of the game. Policy-based interventions can be a significant lever in systems change. Europe’s Green Deal policies comprise a package of policy initiatives to make the continent a sustainability leader and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

For energy, this means incentivizing renewable energy and establishing energy independence from fossil fuels. Companies can join coalitions such as We Mean Business to have a voice in policymaking. Leading companies call on governments to accelerate the transition and suggest stricter policy measures. For example, in May 2022, before the publication of Europe’s energy plan, over 150 companies called on policymakers to strengthen energy security and transition away from fossil fuels – policy advocacy efforts aimed at signaling to governments that change is needed and urgent.

These decisions will significantly impact the company’s performance, competitive advantage, and the overall pace of the transition.

The questions brought up by social science are fundamental to any company in the middle of the energy transition. Decades of social science research demonstrate that in any transition, the incumbents and the disruptors must make numerous strategic choices. These decisions will significantly impact the company’s performance, competitive advantage, and the overall pace of the transition. Since transitions impact entire industries, the stakes are high, with far-reaching consequences that extend financially, environmentally, and socially.

With the increasing number of climate-related natural disasters, supply chains and societies worldwide suffer the consequences of a warming planet. Making a sound strategy based on informed decisions can put executives at ease and accelerate the pace of change.

Authors

Amanda Williams

Research fellow at IMD Business School

Amanda Williams is a research fellow at IMD Business School. She was formally a senior researcher at ETH Zurich, a research fellow at Copenhagen Business School, and a Research Associate at the World Business Council for Sustainable Development where she worked on the SDG Compass, a guide for corporate action on the SDGs. Her research focuses on how organizations understand global sustainability issues and develop corporate sustainability strategies that align with global sustainability targets.

Knut Haanaes

Lundin Chair Professor of Sustainability at IMD

Knut Haanaes is a former Dean of the Global Leadership Institute at the World Economic Forum. He was previously a Senior Partner at the Boston Consulting Group and founded their first sustainability practice. At IMD he teaches in many of the key programs, including the MBA, and is Co-Director of the Leading Sustainable Business Transformation program (LSBT) and the Driving Sustainability from the Boardroom (DSB) program. His research interests are related to strategy, digital transformation, and sustainability.

Related

Riding the duck curve: A strategic guide for companies in the evolving energy landscape

May 27, 2025 in Energy

With solar power flooding grids, the duck curve creates both challenges and opportunities for businesses. Learn how smart companies can harness this shift to cut costs and boost efficiency....

5 things to know about the energy transition in 2025

April 24, 2025 in Energy

Despite headwinds from policy shifts and market pressures, the clean energy transition is gaining pace. Here are five key insights for business leaders on where it stands in 2025....