A Discovery Event in June 2015 stimulated discussion of the broad changes in the Indian economic landscape as the Narendra Modi-led reform-minded, pro-business government completed its first year in office. A panel of speakers took stock, both at the macro policy initiatives level and at the business impact level.

In a watershed event in India’s electoral history, a majority government came to power in May 2014 after three decades of coalition governments. The new prime minister, Narendra Modi, had struck a chord with the masses as well as with corporate India based on his campaign promise to usher in a new era of economic and political reforms by dealing with rampant corruption, opening up the economy, creating jobs, and easing the pain of conducting business in the country. With the initial euphoria, India’s benchmark S&P BSE Sensex Index was among the top gainers globally, rallying 30% in 2014 as investors poured a record $42 billion into Indian stocks and bonds. Falling oil prices helped reduce double-digit inflation rates to 5%, and revised GDP figures put India’s growth on a par with China’s.

After a year in office, it was timely to explore India’s economic agenda. Was it progressing or regressing? The overall enthusiasm about the government’s ability to deliver change – and fast – seemed to be fading as the opposition in parliament stalled two major economic proposals. First was the long-pending legislation to overhaul India’s chaotic system of local and state taxes and create a unified national goods and services tax (GST). Second was the amendment to the land acquisition bill, which would allow the government to acquire land for essential infrastructure development projects. This was proving to be a challenge in a democratic and agrarian society. These setbacks were causing disappointment, impatience and serious doubts among business groups about the government’s ability to modernize India’s economy and administrative framework.

Yet Professor Dhanaraj was optimistic that India held a lot of promise: GDP had grown 4.5 times, from $481 billion at the turn of the millennium to $2.1 trillion in 2014/15, against a backdrop of high inflation. To realize this promise, he shared a “Four P” framework for strategic decision making and action:

- Portfolio: Think about India in your portfolio. When working with volatile markets in a complex economy, you are not going to get it right all the time. A diversified portfolio is critical to cover the risks.

- Persistence: There will be problems. Get over the initial shock and take time to work through them.

- Pragmatism: This is not compromise but rather understanding the context, avoiding stereotypes and continuing to go back and forth.

- Partnership: Invest to build trust with partners – they can open doors for you. The risk of not working with partners is greater than the risk of a bad partnership.

Participants were keen to understand how their companies could navigate for success with regard to: (1) gaining traction on policy changes for trade and investment; (2) overcoming human capital challenges; (3) gaining insights into consumer profiles; and (4) selling India as a growth story within their organization.

1. Policy changes for trade and investment

Ravindra Jaiswal highlighted some of the early indicators of turnaround in the Indian economy. GDP increased to over 7% (in line with IMF predictions), while the fiscal deficit was contained at 4% of GDP in 2014/15. For the first time, 100% foreign investment in railway infrastructure projects was approved, and the foreign investment cap in defence was hiked from 26% to 49%. The Insurance Bill (pending since 2008) was passed and India raised a record $17.6 billion through a telecom spectrum auction. The Coal Ordinance 2014 ended a 40-year government monopoly on mining and selling coal, and enabled commercial mining by Indian and foreign companies, states and private joint ventures. The retail sector also witnessed increasing investments from global companies.

Financial inclusion received a boost through the prime minister’s Jan Dhan Yojna initiative, whereby government banks were ordered to open an account for every family, into which subsidies and cash transfers could be paid directly. This would eliminate corruption and leakages in existing anti-poverty schemes. The Modi administration also scrapped diesel subsidies and reduced allocations to agriculture-allied areas and social sectors to rein in a subsidy bill that had surged fivefold over the previous decade. Instead, these schemes would be supported by state governments through an increased allocation of central taxes from the government.

The freed-up funds were put into infrastructure development – roads, bridges, highways and ports – to spur an economy in which private investment as a share of GDP had fallen to the lowest level in a decade. Professor Dhanaraj explained India’s cautious stance on opening up the economy for foreign investment. “Given its colonial history, the country remains apprehensive, and efforts in this direction invariably cause great media hype that questions whether FDI comes with a price tag.”

A flagship “Make in India” campaign was launched to make India a global manufacturing hub. Compared with countries like China, Korea and Indonesia, where the share of manufacturing is 40% to 50% of GDP, India’s is 15%. Twentyfive industries have been identified for investment to provide a vital impetus for employment and growth. According to Chandrasekhar Sripada, global head of HR at Dr Reddy’s, India skipped the manufacturing step in its economic journey, moving directly from agriculture to services. India needs to revive product innovation and create a strong manufacturing environment. In an attempt to improve India’s rank of 134 out of 182 countries by 50 places in the World Bank’s “Ease of Doing Business” index, Modi reduced the number of procedures and permits required to set up a business, thus cutting the red tape.

MNCs are being invited to manufacture in India as an alternative to China (irrespective of whether the products are to be sold in India or abroad). Michele Enderle, who as director of the Swiss Business Hub in Mumbai, experienced these policy changes on the ground said that although it was easier to gain access to ministries to discuss projects, companies still had to spend time building relationships and leveraging technology, know-how and the workforce. Also, there are no additional incentives to attract firms to “Make in India.” Norbert Raschle of PwC noted that the service sector is easier to enter, as demonstrated by ICT companies and banks that have already established huge operations. However, MNCs will need to think about how much IP/know-how to relocate to India because of profit allocation issues – previously, ownership of R&D was driven by the HQ and profit flowed to them, but in future the profit allocation will likely shift as more work and R&D decision making takes place in the country.

2. Human capital challenges

The scale and diversity of the human capital in India is staggering as the country reaps the demographic dividend: 65% of the country’s population of 1.25 billion people is under 35 years old, and 50% is under 25. For businesses, this has implications in terms of both the talent pool and target consumer segments with higher purchasing power and a propensity to spend. Participants’ key concerns about human capital and speakers’ responses were as follows:

Attrition of people and knowledge: According to Dr Chandrasekhar, a common defining trait of young Indians is ambition. The generation entering the workforce has experienced high economic growth since the turn of the century. The fast growth of the IT/business process outsourcing/service sector has resulted in a boom in employment opportunities, with some companies even paying a retention bonus for the first five years. The young generation do not hide their ambition and are not willing to wait – in fact, cut-throat competition is the norm. If companies can harness this, they will get hard work, long hours and compliance in return. To deal with attrition, companies need to define a practical and acceptable employee turnover level, segment the causes of attrition and address those that can be handled and ignore the rest.

The “unemployability” of hundreds and thousands of entry level graduates: The Indian university system has a processoriented theoretical approach. Professor Narasimhan compared it to a conveyor belt onto which students jump and – ready or not – emerge at the other side to enter the workforce. As thousands of graduates queue for every opportunity, the talent pool becomes homogeneous – with more commonality than diversity. With adequate training, this pool can work well in domestic organizations, but they often cannot manage a global business. Contemplating the readiness of domestic employees for global challenges, Professor Narasimhan asked participants, “Are your companies acquirers of talent or are you willing to invest? India made the initial investment in human capital, and Western companies sought to reap the benefits at low cost. With the externalization of talent, the question is who is subsidizing whom.”

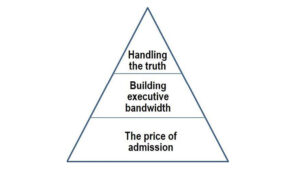

Inadequate feedback culture: Corporate life in India has largely been modeled on Western capitalist companies with, for example, classification of employees into grades, goal setting, mid-year reviews, rewarding the best performers with higher salary increases and vice versa. But culture has mediated in a way that makes the operationalization different. Professor Narasimhan agreed that hierarchy continues to be a stumbling block in developing a culture of open communication: Subordinates do not challenge or speak their mind, while bosses prefer not to give negative feedback. At the same time, top level leaders are not open to feedback. Therefore, managers needed to be trained in people skills, particularly to give feedback and manage the expectations of a young workforce. He urged MNCs to recognize and deal with specific talent challenges at three levels of the organization as shown in Figure 1.

Be the kingpin seeker. To be powerful you have to share power but people don’t know how to do that. They are not socialized into doing that.

3. Consumer profiles

The Indian consumer market is the 12th largest in the world, and consumer spending accounts for nearly 60% of GDP, comparable to countries such as the UK, the US and France. India is at a juncture where people are willing to experiment. The “Indian at heart, Global in spirit” slogan at Mumbai international airport captures the mindset change among the young, educated masses. The current trend is to create a new fusion culture by inviting and imbibing global cultures. And according to Professor Challagalla, Indian consumers are feeling the impact of globalization.

To understand how to translate numbers, such as 200 million educated urban dwellers or 700 million rural inhabitants, into revenues, it is essential to understand the psyche of the Indian consumer. With increased brand consciousness, companies need to position their brands to capture the imagination of consumers, which mainly revolves around education and status. The current pace of economic change is 5 to 10 times faster than at any point in history, and 4.5X growth has given India a new level of confidence which is seen in a shift in consumer attitudes (see Table 1).

| Previous | Current |

| Karma-destiny, accept it | Kshatriya values- I can shape my destiny |

| Knowledge- mind over matter | Winning |

| Patience- one step at a time | Achieve quickly |

| Simplicity- live within your means | Higher propensity to spend |

| Modesty- social approval and restraint | Show what you have but social approval is still important |

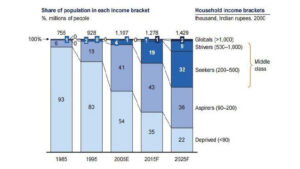

Referring to a classification of Indian consumers as shown in Figure 2, Professor Challagalla noted that MNCs have an edge in targeting Globals as this group is educated, brand conscious and has sufficient disposable income. The middle class, comprising Strivers and Seekers, is the battleground between domestic companies and MNCs. With regard to Aspirers and the Deprived, MNCs are struggling to gain a foothold as their value proposition is not aligned with the needs and realities of these consumers. Competition for discretionary spending is expected to play out in healthcare, education, recreation and communication. Indian e-commerce is still at a nascent stage, but the sector had been growing at 35% CAGR, from $3.8 billion in 2009 to $12.6 billion in 2013.

4. Selling India as a growth story within the organization

In a fast-paced volatile environment, companies react in two different ways: either they try to hold on to the past, at the risk of becoming irrelevant, or they move rapidly to shape their own future and achieve 10 X 10, i.e. 10 times growth in 10 years. Michael Enderle highlighted three points: (1) India has to be considered in the business portfolio – be it as a manufacturing location or a target market; (2) talent availability will add value to increase business competitiveness; and (3) India can serve as an experimental bed for R&D.

To transfer learning from the India growth story that unfolded in the middle of the global recession, Professor Malnight shared a case study on Mahindra & Mahindra Financial Services Ltd (Mahindra Finance), part of India’s $16.9 billion Mahindra & Mahindra Group (M&M), which ranked among the top ten industrial houses in the country. In contrast to a conglomerate, M&M functioned as a federation of companies at different stages of growth. At the group level, M&M worked to build the ecospace by identifying distinct opportunities. It then enabled/facilitated the next level of leadership to pursue the company-level strategy. Between the core and the periphery, there was a fine balance of autonomy and control.

Mahindra Finance was created by M&M in 1995 to provide finance to rural and semi-urban India. Mahindra Finance believed in building new markets rather than entering new businesses. It successfully created new markets over and over again by embedding customercentricity in its business model. Instead of force-fitting standard finance products, the company designed/customized its products and services to address real customer needs. It started with vehicle financing, moved into insurance broking then home financing, and is currently pushing through into SME financing. Creating an environment for experimentation, failure and coursecorrection on the way allowed Mahindra Finance to achieve growth of 30% CAGR year-on-year for two decades.

Success is possible

By the end of the day, and equipped with the Four P framework of portfolio, persistence, pragmatism and partnership, participants were more enlightened about the impact of Narendra Modi’s changes during his first year in office and how they could steer their companies on a successful course in India.

Discovery Events are exclusively available to members of IMD’s Corporate Learning Network. To find out more, go to www.imd.org/cln